Migrating Netdelta From Docker to Kubernetes

In latish 2020, I moved Netdelta from a Docker deployment to Kubernetes, partly to see what all this Kubernetes jazz is about, and partly to investigate whether it would help me with the management of Netdelta containers for different punters, each of whom has their own docker container and Apache listening service.

I studiously went through the Kubernetes quick tutorial and found i had to investigate the documentation some more. Even then some aspects weren’t covered so well. This post explains what i did to deploy an app into Kubernetes, and some of the gotchas i encountered along the way, that were not covered so well in the Kubernetes documentation, and I summarise with a view of Kubernetes and give my view on: is the hype justified? Will I continue to host Netdelta in Kubernetes?

This is not a Kubernetes tutorial – it does assume some prior exposure on behalf of the reader, but nonethless links to the relevant documentation when some Kubernetes concepts are covered.

Contents

- Netdelta in Docker

- Data Flows / Networking

- Reverse Proxy

- K8s Nginx Ingress Controller

- DNS

- The Application Hosting for Kubernetes

- PV Mounts

- Database and Fileserver

- To K8s Or Not To K8s?

Netdelta in Docker

This post isn’t about Netdelta, but for illustrative purposes: Netdelta aids with the detection of unauthorised changes, and hacker shells, by running one-off port scans, or scheduled jobs, comparing the results with the previous scan, and alerting on changes. This is more chunky than it sounds, mostly because of the analytics that goes into false positives detection. In the Kubernetes implementation, scan results are held in a stateful persistent volume with MySQL.

Netdelta’s docker config can be dug into here, but to summarise the docker setup:

- Database container – MySQL 5.7

- Application container – Apache, Django 3.1.4, Celery 5.0.5, Netdelta

- Fileserver (logs, virtualenv, code deployment)

- Docker volumes and networking are utilised

Data Flows / Networking

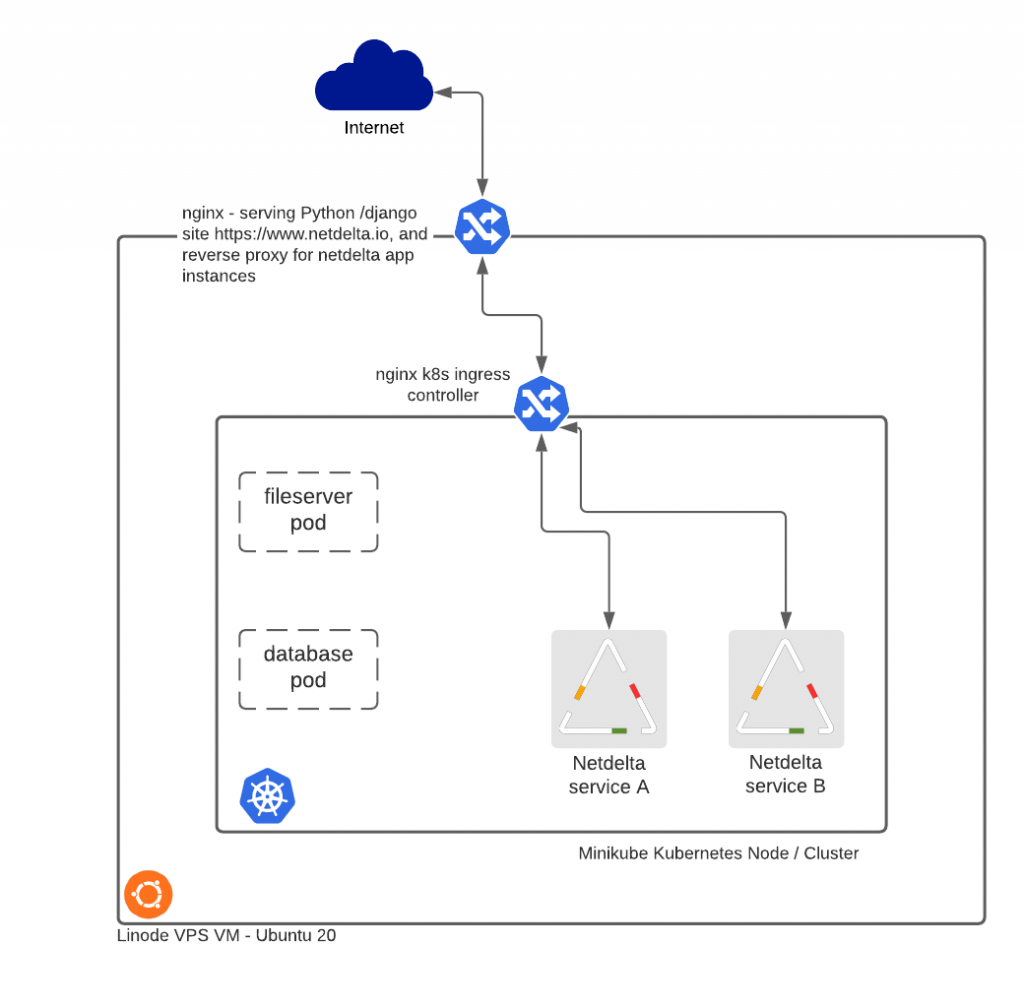

The data flows aspect reflects what is not exactly a bare metal deployment. A Linode-hosted VM running Ubuntu 20 is the host, then the Kubernetes node is minikube, with another node running on a Raspberry pi 3 – the latter aspect not being a production facility. The pi 3 was only to test how well the config would work with load balancing, and Kubernetes Replicasets across nodes.

Reverse Proxy

Ingress connections from the internet are handled first by nginx acting as a reverse proxy. Base URLs for Netdelta are of the form https://www.netdelta.io/<site>. The nginx config …

server {

listen 80;

location /barbican {

proxy_set_header Accept-Encoding "";

sub_filter_types text/html text/css text/xml;

sub_filter $host $host/barbican;

proxy_pass http://local.netdelta.io/barbican;

}

}

K8s Ingress Controller

This is passing a URL with a first level of <site> to be processed at local.netdelta.io, which is locally resolvable, and is localhost. This is where the nginx Kubernetes Ingress Controller comes into play. The pods in kubernetes have NodePorts configured but these aren’t necessary. The nginx ingress controller takes connections on port 80, and routes based on service names and the defined listening port:

┌──(iantibble㉿bionic)-[~]

└─$ kubectl describe ingress

Name: netdelta-ingress

Namespace: default

Address: 172.17.0.2

Default backend: default-http-backend:80 (<error: endpoints "default-http-backend" not found>)

Rules:

Host Path Backends

---- ---- --------

local.netdelta.io

/barbican netdelta-barbican:9004 (<none>)

Annotations: <none>

Events: <none>

The YAML looks thusly:

┌──(iantibble㉿bionic)-[~/netdd/k8s]

└─$ cat ingress.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: netdelta-ingress

spec:

rules:

- host: local.netdelta.io

http:

paths:

- path: /barbican

backend:

service:

name: netdelta-barbican

port:

number: 9004

pathType: Prefix

So the nginx ingress controllers sees the connection forwarded from local.netdelta.io with a URL request of local.netdelta.io/<site>. The requests matches a rule, and forwards to the Kubernetes Service of the same name. The entity that actually answers the call is a docker container masquerading as a Kubernetes Pod, which is part of a deployment. The next step in the data flow is to route the connection to the specified Kubernetes Service which is covered briefly here but in more detail later in the coverage of DNS.

The “service” aspect has the effect of exposing the pod according to the service setup:

┌──(iantibble㉿bionic)-[~/netdd/k8s] └─$ kubectl get services -o wide NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE SELECTOR kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 443/TCP 119d mysql-netdelta ClusterIP 10.97.140.111 3306/TCP 39d app=mysql-netdelta netdelta-barbican NodePort 10.103.160.223 9004:30460/TCP 36d app=netdelta-barbican netdelta-xynexis NodePort 10.102.53.156 9005:31259/TCP 36d app

DNS

There’s an awful lot of waffle out there about DNS and Kubernetes. Basically – and I know the god of devops won’t let me in heaven for saying this, but making a service in Kubernetes leads to DNS being enabled. DNS in a multi-namespace, multi-node scenario becomes more intreresting of course, and there’s plenty you can configure that’s outside the scope of this article.

Netdelta’s Django settings.py defines a host and database name, and has to be able to find the host:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.mysql', # Add 'postgresql_psycopg2', 'mysql', 'sqlite3' or 'oracle'.

'NAME': 'netdelta-SITENAME', # Not used with sqlite3.

'USER': 'root', # Not used with sqlite3.

'HOST': mysql-netdelta,

'PASSWORD': 'NOYFB',

'OPTIONS': dict(init_command="SET sql_mode='STRICT_TRANS_TABLES,NO_ZERO_IN_DATE,NO_ZERO_DATE,ERROR_FOR_DIVISION_BY_ZERO,NO_AUTO_CREATE_USER'"),

}

}

This aspect was poorly documented and was far from obvious: the spec.selector field of the service should match the spec.template.metadata.labels of the pod created by the Deployment.

The Application Hosting in Kubernetes

Referring back to the diagram above, there are pods for each Netdelta site. How was the Docker-hosted version of Netdelta represented in Kubernetes?

The Deployment YAML:

apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: Deployment metadata: creationTimestamp: null labels: app: netdelta-barbican name: netdelta-barbican spec: replicas: 1 selector: matchLabels: app: netdelta-barbican strategy: type: Recreate template: metadata: creationTimestamp: null labels: app: netdelta-barbican spec: containers: - image: registry.netdelta.io/netdelta/barbican:1.0 imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent name: netdelta-barbican ports: - containerPort: 9004 args: - "barbican" - "9004" - "le" - "certs" resources: {} volumeMounts: - mountPath: /srv/staging name: netdelta-app - mountPath: /srv/logs name: netdelta-logs - mountPath: /le name: le - mountPath: /var/lib/mysql name: data - mountPath: /srv/netdelta_venv name: netdelta-venv imagePullSecrets: - name: regcred volumes: - name: netdelta-app persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: netdelta-app - name: netdelta-logs persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: netdelta-logs - name: le persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: le - name: data persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: data - name: netdelta-venv persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: netdelta-venv restartPolicy: Always serviceAccountName: "" status: {}

Running:

kubectl apply -f netdelta-app-<site>.yaml

Has the effect of creating a pod and a container for the Django application, celery and Apache stack:

┌──(iantibble㉿bionic)-[~] └─$ kubectl get deployments NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE fileserver 1/1 1 1 25d mysql-netdelta 1/1 1 1 25d netdelta-barbican 1/1 1 1 25d ┌──(iantibble㉿bionic)-[~] └─$ kubectl get pods NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE fileserver-6d6bc54f6c-hq8lk 1/1 Running 2 25d mysql-netdelta-5fd7757c66-xqp2j 1/1 Running 2 25d netdelta-barbican-68d78c58bd-vnqdn 1/1 Running 2 25d

K8s Equivakent of Docker Entrypoint Script Parameters

Some other points perhaps worthy of mention were around the Docker v Kubernetes aspects. My docker run command for the netdelta application container was like this:

docker run -it -p 9004:9004 --network netdelta_net --name netdelta_barbican -v netdelta_app:/srv/staging -v netdelta_logs:/srv/logs -v data:/data -v le:/etc/letsencrypt netdelta/barbican:core barbican 9004 le certs

So there’s 4 parameters for the entryscript: site, port, le, and cert. The last two are about letsencrypt certs which won’t be covered here. These are represented in the Kubernetes Deployment YAML in spec.template.spec.containers.args.

Private Image Repository

spec.template.spec.containers.image is set to registry.netdelta.io/netdelta/<site>:<version tag>. Yes, that’s right folks, i’m using a private registry, which is a lot of fun until you realise how hard it is to manage the images there. The setup and management of the private registry won’t be covered here but i found this to be useful.

One other point is about security and encryption in transit for the image pushes and pulls. I’ve been in security for 20 years and have lots of unrestricted penetration testing experience. It shouldn’t be necessary or mandatory to use HTTPS over HTTP in most cases. Admittedly i didn’t spend long trying, but i could not find a way to just use good old clear-text port 80 over 443, which in turn meant i had to configure a SSL certifcate with all the management around it, where the risks are far from justifying such a measure.

PV Mounts

In Dockerland I was using Docker Volumes for persistent storage of logs and application data. I was also using it for the application codebase, and any updates would be sync’d with containers by docker exec wrapped in a BASH script.

There was nothing unexpected in the deployment of the PVCs/PVs, but a couple of points are worth mentioning:

- PV Filesystem mounts: Netdelta container deployment involves a custom image from COPY (Docker command) of files from a local source to the image. Then the container is run and the application can find the required files. The problem i ran into was about having filesystems mounted over the directories where my application container expected to find files. This meant i had to change my container entryscript to sync with the image when the Pod is deployed, whereas previously the directories were built-out from the docker image build.

- /tmp as default PV files location: if you SSH to the node (minikube container in my case), you will find the mounted filesystems under /tmp. /tmp is a critical directory for the good health of any Linux-based system and it needs to be 777 (i.e. read and writeable by unauthenticated users and processes) with a sticky bit. This is one that for whatever reason doesn’t find its way into security checklists for Kubernetes but it really does warrant some attention. This can be changed by customising Kubernetes Storage Classes. There’s one pointer here.

Database and Fileserver

The MySQL Database service was deployed as a custom built container with my Docker setup. There was no special reason for this other than to change filesystem permissions, and the fact that the listening service needed to be “exposed” and the database config changed to bind to 0.0.0.0 instead of localhost. What i found with the Kubernetes Pod was that I didn’t need to change the Mysql config at all and spec.ports.targetport had the effect of “exposing” the listening service for the database.

The main reason for using a fileserver in the Dcoker deployment of Netdelta was to act as a container buffer between Docker Volumes and application containers. My my Unix hat on, one is left wondering how filesystem persmissions will work (or otherwise) with file read and writes across network mounted disparate unix systems, where even if the same account names exist on each system, perhaps they have different UIDs (BSD-derived systems use the UID to define ownership, not the name on the account). Moreover it was advised as a best practice measure in the Docker documentation to use an intermediate fileserver. Accordingly this was the way i decided to go with Kubernetes, with a “sidecar” Pod as a fileserver, which mounts the PVs onto the required mount points.

To K8s Or Not To K8s?

When you think about the way that e.g. Minikube is deployed – its a docker container. If you run a docker ps -a, you can see all the mechanics at work. And then if you SSH to the minikube, you can do another docker ps -a, and you see everything to do with Kubernetes pods and containers in the output. This seems like a mess, and if it isn’t, it will do until the mess actually arrives.

Furthermore, you don’t even want to look at the routing tables or network interfaces on the node host. You just cannot unsee that.

There is some considerable complexity here. Further, when you read the documentation for Kubernetes, it does have all the air of documentation written by programmers. We hear a lot about the lack of IT-skilled people, but what is even more lacking, are strategic thinkers (e.g. * [wildcard] Architects) who translate top level business design requirements into programming tactical requirements.

Knowing how Kubernetes works should be enough to know whether it’s really going to be beneficial or not to host your containers there. If you’re not sure you need it, then you probably don’t. In the case of Netdelta, if i have lots and lots of Netdelta sites to manage then i can go with Kubernetes, and now that i have seen Netdelta happily running in Kubernetes with both scheduled celery jobs and manual user-initiated scans, the transition will be a smooth one. In the meantime, I can work with Docker containers alone, with the supporting BASH scripts, whuch are here if you’re interested.

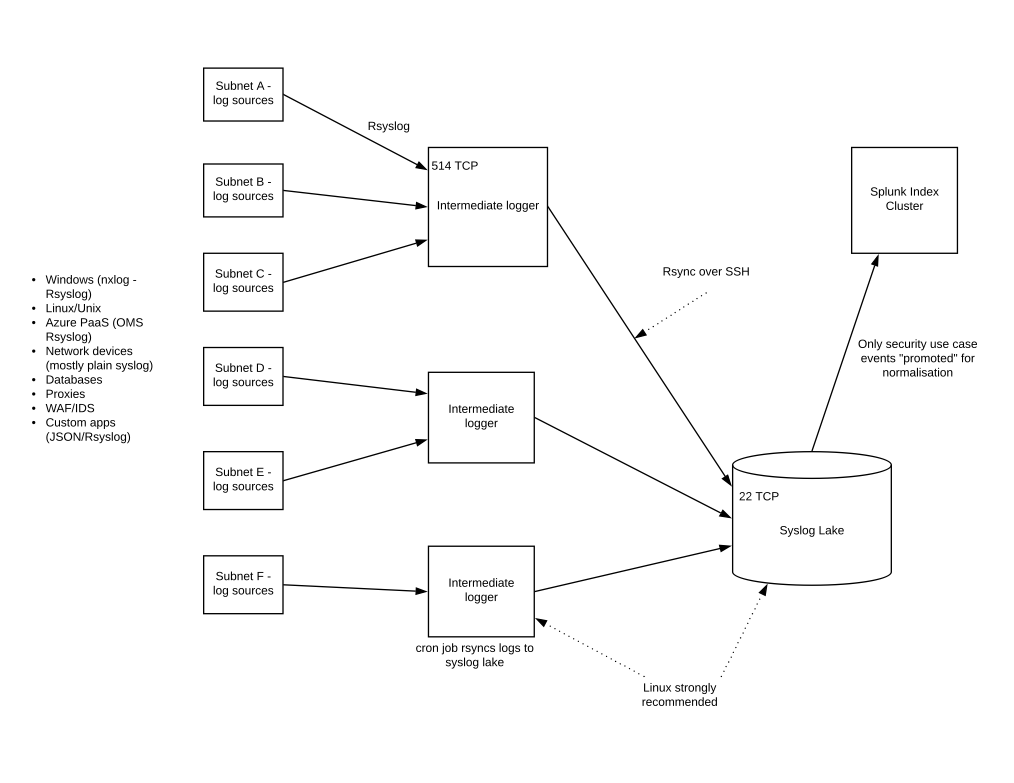

This can be a problem if you decide to go with a COTS where licensing costs are based on volume of events. Also, you cannot turn on OS events that you could be interested in. The way CSPs play here is to assume everything is interesting, which can get expensive. Very expensive.

This can be a problem if you decide to go with a COTS where licensing costs are based on volume of events. Also, you cannot turn on OS events that you could be interested in. The way CSPs play here is to assume everything is interesting, which can get expensive. Very expensive.

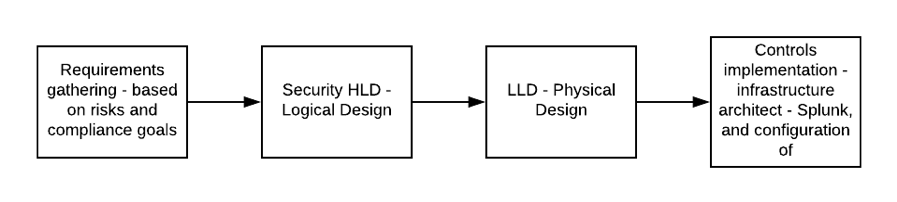

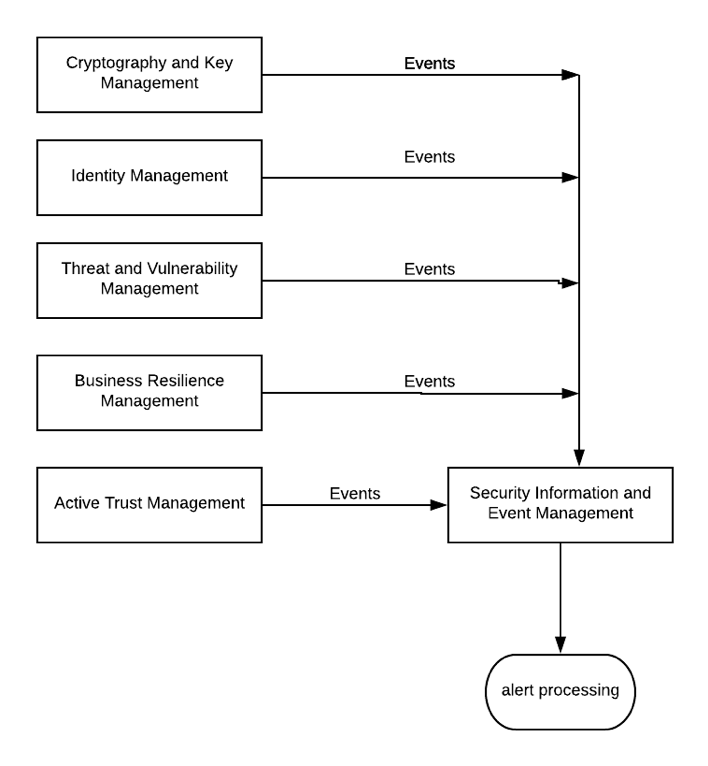

Whenever you are trying to build something complex with lots of moving parts, architecture is used to reduce the problem down to a manageable size, and help to build good practices in risk management. The end goal is protective monitoring of an infrastructure that is built with requirements for meeting both risk and compliance challenges.

Whenever you are trying to build something complex with lots of moving parts, architecture is used to reduce the problem down to a manageable size, and help to build good practices in risk management. The end goal is protective monitoring of an infrastructure that is built with requirements for meeting both risk and compliance challenges.